In mid-September, the Edmonton Journal ran a feature looking at downtown development in Edmonton, noting the nearly $5 billion in buildings going into Edmonton’s downtown and adjacent neighbourhoods by the end of this decade. According to one of the sources in the article, this kind of development is “unprecedented” and “unheard of” and further, “people haven’t grasped the significance of it.”

In a province and a city where the cycle of boom and bust is regarded as the rhythm of life itself, this activity should be equal parts impressive and troubling. All of this is bound to change the downtown, but what will it mean for Edmonton’s memory and heritage as a city? In the midst of another transformation of downtown, is it possible for people connect to what was there before (and before that and before that) and how all of this came to be?

While we need to do more around the city’s built heritage, the current challenge is how to infuse memory and experience into these new spaces even as the concrete is setting. In early September 2014, Oilers VP Bob Nicholson enthused over the new Arena District, “it will be like going to Disneyland”, noting the different aspects of the project that will connect with people.

Leaving aside the “Disneyland” notion, let’s agree that the heritage of that district is one of those connections to be made with people in the new districts. Rogers Place is built wholly on top of “The Yards”—an area essential to understanding Edmonton’s story. It’s part of the place where generations of immigrant families arrived in Edmonton by rail, disembarking to the nearby Immigration Hall (now repurposed by Hope Mission), one of just three Immigration Halls constructed after the First World War still standing in Canada. It’s the reason that 107th Avenue is the “Avenue of Nations”, where many Edmonton immigrant communities established themselves in their early history of settlement and adjustment. It’s part of the essential Edmonton experience for thousands of Edmontonians and their descendants.

For each of the “projects” noted in the Edmonton 2020 piece in the Edmonton Journal— some connected to the Arena District such as the Station Lands, and others distinct such as Blatchford, The Quarters, West Rossdale—there’s compelling story and reason to ensure that the layers of memory, history and experience of these places connects with people.

How can this be done? Some of it still needs to be done through building preservation and re-purposing, and we should do that wherever we can. But that’s not enough. For new and old developments, we need a manageable and enduring way to fuse memory into the “transformation” of downtown Edmonton.

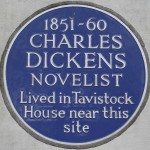

- “Charles Dickens” by Christian Lüts from Flickr under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. https://flic.kr/p/66HjQ8

- “Jimi’s House” by Iain Mullan from Flickr under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. https://flic.kr/p/AFVBv

Perhaps part of the answer for Edmonton lies in London. For the past 150 years, London’s blue plaque scheme has identified the people and events connected to the city’s built heritage. The plaque design is simple. It doesn’t require passers by to stop and read (not that there’s anything wrong about that), but to merely notice and remember. If one wishes more on the associated story that can increasingly be found through smartphone and Internet technology. This is one possible approach to embedding memory into these projects that are transforming Edmonton.

A policy that parallels our civic public art program would be an ideal way to establish this approach in these developments. In fact, it could be easily done for a modest portion of the Percent for Art Program—at LRT stations, in public spaces adjacent to new developments, and for that matter throughout Edmonton where there’s active pedestrian life (that’s perhaps the most limiting factor in this). Connecting to this memory points to a richer transformation by the end of this decade, and one that transcends the boom and bust cycle.